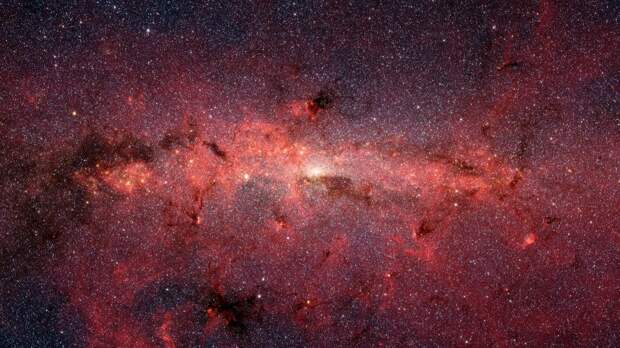

Dark matter with less mass could be driving a mysterious glow emanating from the Milky Way’s core.

Astronomers have long been puzzled by two strange phenomena at the heart of our galaxy. First, the gas in the central molecular zone (CMZ), a dense and chaotic region near the Milky Way’s core, appears to be ionized (meaning it is electrically charged because it has lost electrons) at a surprisingly high rate.

Second, telescopes have detected a mysterious glow of gamma rays with an energy of 511 kilo-electronvolts (keV) (which corresponds to the energy of an electron at rest).

Interestingly, such gamma rays are produced when an electron and its antimatter counterpart—all fundamental charged particles have antimatter versions of themselves that are near identical, but with opposite charge—the positron, collide and annihilate in a flash of light.

The causes of both effects have remained unclear, despite decades of observation. But in a new study, published in Physical Review Letters, my colleagues and I show that both could be linked to one of the most elusive ingredients in the universe: dark matter. In particular, we propose that a new form of dark matter, less massive than the types astronomers typically look for, could be the culprit.

Hidden Process

The CMZ spans almost 700 light years and contains some of the most dense molecular gas in the galaxy. Over the years, scientists have found that this region is unusually ionized, meaning the hydrogen molecules there are being split into charged particles (electrons and nuclei) at a much faster rate than expected.

This could be the result of sources such as cosmic rays and starlight that bombard the gas. However, these alone don’t seem to be able to account for the observed levels.

The other mystery, the 511-keV emission, was first observed in the 1970s, but still has no clearly identified source. Several candidates have been proposed, including supernovas, massive stars, black holes, and neutron stars. However, none fully explain the pattern or intensity of the emission.

We asked a simple question: Could both phenomena be caused by the same hidden process?

Dark matter makes up around 85 percent of the matter in the universe, but it does not emit or absorb light. While its gravitational effects are clear, scientists do not yet know what it is made of.

One possibility, often overlooked, is that dark matter particles could be very light, with masses just a few million electronvolts, far lighter than a proton, and still play a cosmic role. These light dark matter candidates are generally called sub-GeV (giga electronvolts) dark matter particles.

Such dark matter particles may interact with their antiparticles. In our work, we studied what would happen if these light dark matter particles come in contact with their own antiparticles in the galactic center and annihilate each other, producing electrons and positrons.

In the dense gas of the CMZ, these low-energy particles would quickly lose energy and ionize the surrounding hydrogen molecules very efficiently by knocking off their electrons. Because the region is so dense, the particles would not travel far. Instead, they would deposit most of their energy locally, which matches the observed ionization profile quite well.

Using detailed simulations, we found that this simple process, dark matter particles annihilating into electrons and positrons, can naturally explain the ionization rates observed in the CMZ.

Even better, the required properties of the dark matter, such as its mass and interaction strength, do not conflict with any known constraints from the early universe. Dark matter of this kind appears to be a serious option.

The Positron Puzzle

If dark matter is creating positrons in the CMZ, those particles will eventually slow down and eventually annihilate with electrons in the environment, producing gamma-rays at exactly 511-keV energy. This would provide a direct link between the ionization and the mysterious glow.

We found that while dark matter can explain the ionization, it may also be able to replicate some amount of 511-keV radiation as well. This striking finding suggests that the two signals may potentially originate from the same source, light dark matter.

The exact brightness of the 511-keV line depends on several factors, including how efficiently positrons form bound states with electrons and where exactly they annihilate though. These details are still uncertain.

A New Way to Test the Invisible

Regardless of whether the 511-keV emission and CMZ ionization share a common source, the ionization rate in the CMZ is emerging as a valuable new observation to study dark matter. In particular, it provides a way to test models involving light dark matter particles, which are difficult to detect using traditional laboratory experiments.

In our study, we showed that the predicted ionization profile from dark matter is remarkably flat across the CMZ. This is important, because the observed ionization is indeed spread relatively evenly.

Point sources such as the black hole at the center of the galaxy or cosmic ray sources like supernovas (exploding stars) cannot easily explain this. But a smoothly distributed dark matter halo can.

Our findings suggest that the center of the Milky Way may offer new clues about the fundamental nature of dark matter.

Future telescopes with better resolution will be able to provide more information on the spatial distribution and relationships between the 511-keV line and the CMZ ionization rate. Meanwhile, continued observations of the CMZ may help rule out, or strengthen, the dark matter explanation.

Either way, these strange signals from the heart of the galaxy remind us that the universe is still full of surprises. Sometimes, looking inward, to the dynamic, glowing center of our own galaxy, reveals the most unexpected hints of what lies beyond.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

The post New Form of Dark Matter Could Solve Decades-Old Milky Way Mystery appeared first on SingularityHub.